Currency swaps are derivative products that help to manage exchange rate and interest rate exposure on long-term liabilities.

A currency swap involves the exchange of interest payments denominated in two different currencies for a specified term, along with the exchange of principles.

The rate of interest in each leg could either be a fixed rate or a floating rate indexed to some reference rate, like the LIBOR.

In a typical currency swap, counterparties will perform the following:

- Exchange equal initial principal amounts of two currencies at the spot exchange rate,

- Exchange a stream of fixed or floating interest rate payments in their swapped currencies for the agreed period of the swap, and then,

- Re-exchange the principal amount at maturity at the initial spot exchange rate.

The currency swap provides a mechanism for shifting a loan from one currency to another or shifting the currency of an asset.

It can be used, for example, to enable a company to borrow in a currency different from the currency it needs for its operations and to receive protection from exchange rate changes with respect to the loan.

Elements of a Currency Swap

There are several important elements in a currency swap that must be agreed upon between the two parties:

Period of the Agreement

Swaps are medium to long-term arrangements, normally covering 2 to 10 years, at the end of which principal is exchanged.

A five-year arrangement is probably the most common.

Currencies Involved

Most currency swaps involve the dollar and one other major currency (euro, sterling, yen, Swiss francs, Canadian dollars, or Australian dollars).

Swaps between two currencies other than the dollar are less common but can be arranged.

Principal Amounts

Swaps are primarily instruments for large organizations only because the amount of currency involved in a swap is large.

Some swaps arranged in conjunction with bond issues have been for even larger amounts.

Interest Rate Basis

Currency swaps, strictly defined, involve an exchange of two fixed interest payment streams (i.e., a fixed- against-fixed swap).

However, currency swaps also can involve:

- A fixed interest rate versus a floating rate index (e.g., LIBOR).

- Two floating rate indices (e.g., six-month sterling LIBOR versus six-month dollar LIBOR).

A currency swap in which at least one payment stream is based on a floating rate index is sometimes called a cross-currency swap:

- A fixed-against-floating swap is a cross-currency interest rate swap.

- A floating-against-floating swap is a currency basis swap.

Interest rates in a swap are determined by negotiation between the two parties and need not be the same as current market rates.

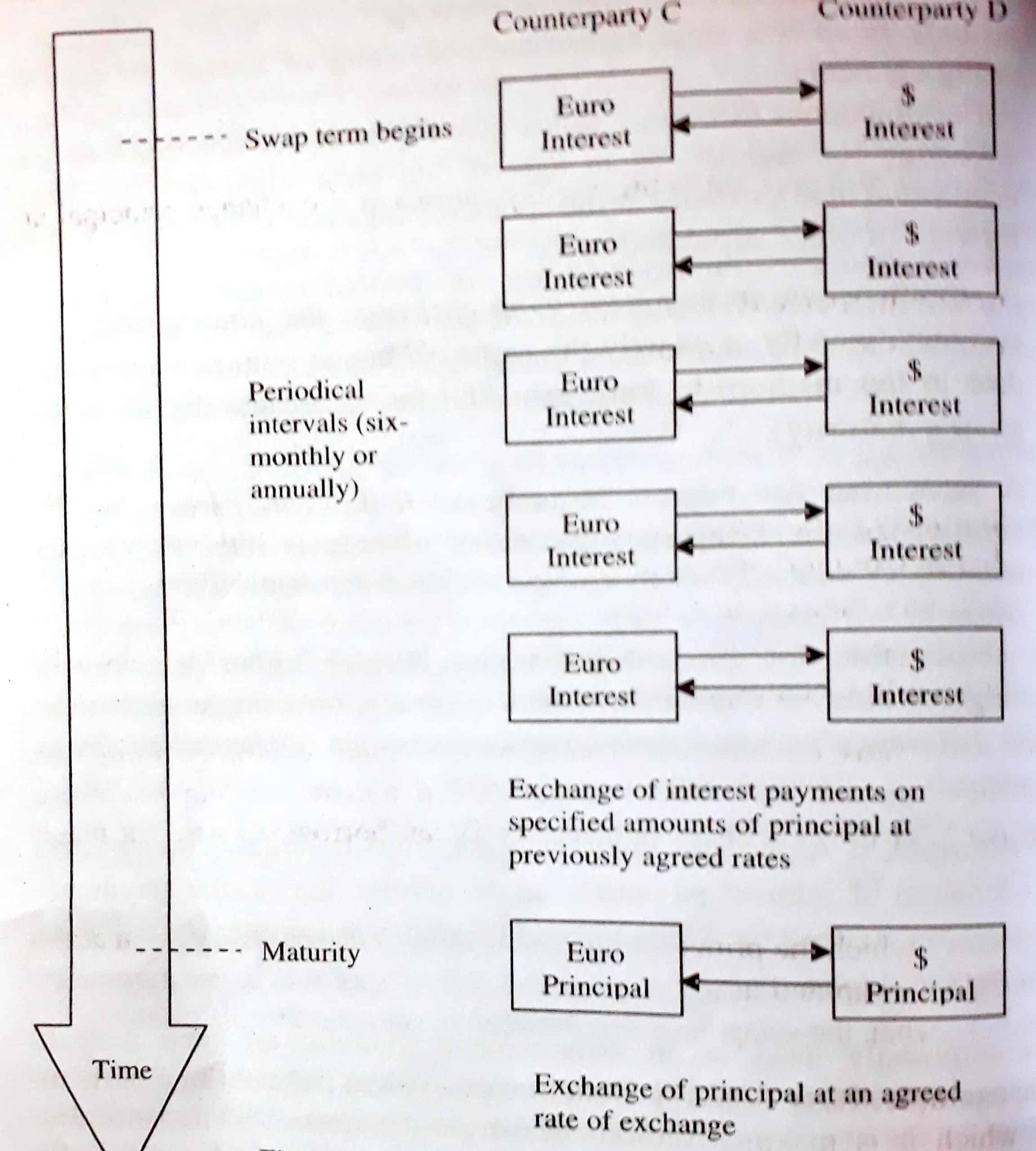

Interest rate payments normally are exchanged at regular intervals, six-monthly, or annually. The amount payable by each party must be specified in the agreement.

This might be a fixed percentage (e.g., 10% annually or 5% every six months) or a floating rate (e.g., the dollar LIBOR rate for six months or 12 months).

Receiver and Payer

Each counterparty to a currency swap can be described in terms of:

- The type of interest (fixed or floating), the currency that he/she pays, and

- The type of interest and the currency that he/she receives.

For example, in a cross-currency interest rate swap, one of the counterparties might be a payer of six-month dollar LIBOR, and a receiver of five-year sterling fixed interest.

(The other counterparty, therefore, will pay five-year sterling fixed interest and receive six-month dollar LIBOR.).

For most currency swaps, one component is the dollar, involving the receipt (or payment) of floating dollars and the payment (or receipt) of a fixed or floating rate in the other currency; e.g., an arrangement to pay 8% in sterling at six-monthly intervals in exchange for receiving interest at six-month dollar LIBOR.

The reason for using dollar LIBOR is that a large proportion of cash-market funding (from banks or commercial paper markets) is based on floating dollar interest rates.

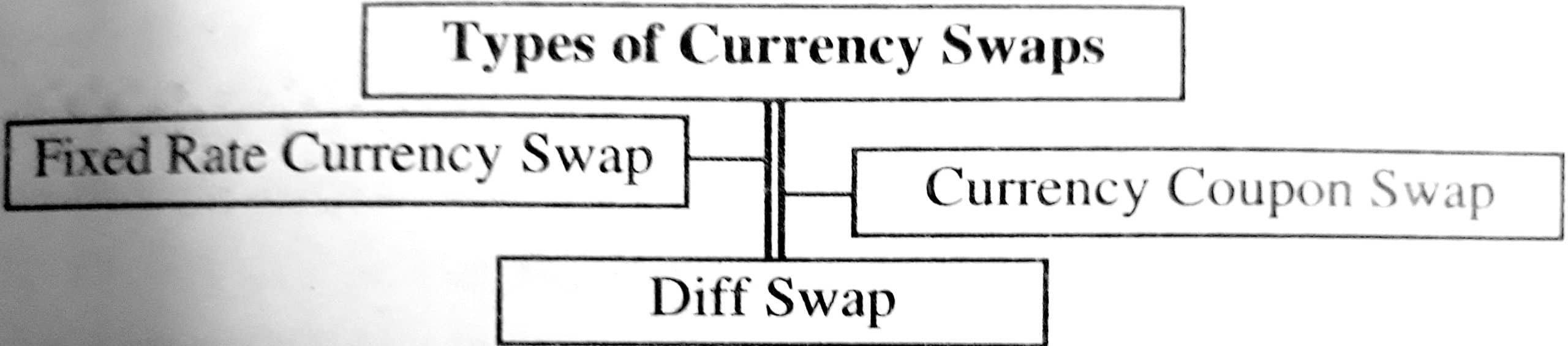

Types of Currency Swaps

Following are the types of currency swaps:

Fixed Rate Currency Swap

A fixed-rate currency swap consists of the exchange between two counter-parties of fixed-rate interest in one currency in return for fixed-rate interest in another currency.

Fixed-to-Fixed Currency Swap

In this category, the currencies are exchanged at a fixed rate. This swap works like this.

One firm raises a fixed-rate liability in currency X, for example, US dollar ($), while the other firm raises fixed-rate funding in currency Y, for example, Pound (£).

The principal amounts are equivalent at the current market rate of exchange. In a swap deal, the first party will get a pound, whereas the second party gets dollars.

Subsequently, the first party will make periodic (pound) payments to the second, in turn, gets dollars computed at interest at a fixed rate on the respective principal amount of both currencies.

At maturity, the dollar and pound principal are re-exchanged.

Fixed-to-Floating Currency Swaps

This swap is a combination of a fixed-to-fixed currency swap and a floating swap.

In this, one party makes the payment at a fixed rate in currency, for example, X, while the other party makes the payment at a floating rate in currency, for example, Y.

Contracts without the exchange and re-exchange of principals do exist. In most cases, a financial intermediary (a swap bank) structures the swap deal and routes the payments from one party to another party.

Currency Coupon Swap

It is a combination of an interest rate swap and a currency swap in which a fixed-rate loan in one currency is swapped for a floating-rate loan in another currency.

A currency swap involves the exchange of an affixed rate obligation in one currency for a floating rate obligation in another currency.

This is known as ‘Fixed to Floating Currency Swap,’ or ‘Circus Swap,’ or ‘Currency Coupon Swap.’

The most important currencies in the currency swap market are the US Dollar, the Swiss Franc, the Deutsche Mark, the ECU, the Sterling Pound, the Canadian Dollar, and the Japanese Yen.

The currency swap is an important tool to manage currency exposures and cost benefits at the same time.

These are often used to provide long-term financing in foreign currencies. This function is important because, in many foreign countries, long-term capital and forward foreign exchange markets are notably absent or not well developed.

However, if the international financial markets were fully developed from all angles, then the incentive to swap would not be so much due to the availability of arbitrage opportunities.

Diff Swap

Another variation of the swap family is the differential swap also commonly known as diff swap or Quanto swap.

This product was first developed in the early nineties in order to suit the needs of customers who had strong views on the spread between interest rates in different countries.

For example, the treasurer of Company A, a US-based company, gets today’s market data for US and Japan’s yield curves.

He thinks that due to the strong growth in the US economy relative to Japan’s, the US interest rates are likely to rise faster than what the market suggests now, i.e., the spread between US interest rates and Japan interest rates would widen even further than today’s prediction.

Benefits of Currency Swaps

Currency swaps are useful in the following respects:

1. Choice: Enabling banks to make loans and accept deposits in the currency of customer choice.

2. Hedge: Allowing banks to hedge any mismatch between forwarding sales and purchases of foreign currency, a currency swap is a series of future exchanges of amounts of one currency for amounts of another.

3. Benefits Firms: Facilitates firms to take out a coupon loan in one currency and change the effective currency or denomination of the loan by one contract.

4. Equilibrium: Enables banks to arrive at an equilibrium app on the currency balances.

5. Low Cost: Reduction in transaction costs if an investor intends to reverse the transaction.

6. Tax Savings: Saying on tax payments may be another objective for engaging in a swap contract by transforming income into capital gains, especially where the capital gains are liable to be taxed.

Mechanics of Currency Swap

A currency swap is a legal agreement consisting of at least two of the following elements:

1. An arrangement to buy or sell a given quantity of one currency in exchange for another, at an agreed rate on a stipulated date (the near-value date), usually at the spot exchange rate (less typically at a forward or other stipulated rate).

2. A simultaneous arrangement to re-exchange the same quantity of currency, usually at exactly the same exchange rate, at a stipulated date in the medium to long-term (the far-value date that is at the swap’s maturity).

3. A settlement for interest costs between the two parties for the duration of the swap, payable either at regular intervals (or six months or annually) or in a single settlement at maturity.

The settlements for interest costs can involve either a two-way exchange of interest payments in each currency or a single settlement of the difference between the two amounts in one of the currencies to the swap.

For example, if Alpha and Beta swap liabilities in dollars and sterling, the exchange of interest payments might involve the regular payments of interest in sterling by Alpha to Beta in exchange for an interest in dollars from Beta to Alpha.

Less commonly used is an arrangement whereby on each interest exchange date, either Alpha or Beta makes a single payment in dollars or sterling to the other as a settlement for the difference in interest rates.

The purpose of these interest payments is to ensure that the finance costs of each party are covered.

Currency swaps need not involve an exchange of principal at the near-value date, in which case there are just two elements to the transaction:

- A regular exchange of interest payments over the swap period.

- An exchange of principal at the far-value date (maturity).

This is illustrated in the figure given below, where the currencies swapped are dollars and euros:

In practice, most swaps do involve an exchange of principal at the near value date, but it is largely immaterial whether this exchange of principal actually takes place or whether it is notional.

To understand how a swap works, consider the following example.

Suppose that Counterparty A wants to take on a liability (i.e., borrow) in one currency, sterling, for a period of several years:

- Paying regular interest in sterling, and

- Making a principal repayment in sterling at the end of the period.

Similarly, Counterparty B wants to assume the same amount of liability but in dollars, for the same period:

- Paying regular interest in dollars, and

- Making a principal repayment in dollars at the end of the period.

Suppose that Counterparty A wants to borrow £10 million Counterparty B wants to borrow, and the exchange rate is $1.50 = £1.

Counterparty A could borrow £10 million in sterling, and Counterparty B could borrow $15 million.

Alternatively, Counterparty A can borrow $15 million dollars. Counterparty B can borrow £10 million, and they can arrange a currency swap.

Under the swap arrangement, the two parties will exchange principal at the near-value date.

1. Counterparty A, having borrowed $15 million, will give the dollars to Counterparty B.

Counterparty B will pay interest to Counterparty A on the $15 million, and at the swap’s maturity (probably scheduled to coincide with the maturity of Counterparty A’s dollar loan), Counterparty B will repay the principal ($15 million) to Counterparty A.

2. Similarly, Counterparty B, having borrowed £10 million, will give this to Counterparty A at the start of the swap. Counterparty A will then pay interest in sterling on this principal to Counterparty B.

At the swap’s maturity, Counterparty A will then pay back the £10 million to Counterparty B.

The swap thus enables each party to exchange a liability from one currency for another.

Counterparty A can borrow sterling but make payments in dollars, and Counterparty B can borrow dollars but make payments in sterling.

The rate at which the principal is exchanged in a currency swap, both at the start of the swap and at maturity, is usually the spot rate at the transaction date (i.e., when the swap is agreed between the counterparties).

For example, Party A has just borrowed the U.S. $10,000,000 for five years, on which it is making floating-rate payments every six months.

The company would have preferred to borrow Indian rupees. To do this, the company engages in a currency swap with another party as follows:

| Tenor | 5 Years |

| Party A | Pay fixed interest in Indian rupees at 6% |

| Party B | Pay floating interest in the U.S. dollars at the LIBOR flat rate. |

| Payments | Every six months |

| Notional | U.S. $10,000,000/ Rs. 40,00,00,000 at the exchange rate of U.S. $1 = Rs. 40 |

At the initiation of the swap, Party A delivers U.S. $10,000,000 notional amount to Party B, and Party B delivers Rs. 40,00,00,000 to Party A.

The initial notional amounts are determined on the basis of the exchange rate prevailing at the initiation of the swap.

The net value of this exchange will be zero. This is equivalent to Party A borrowing Rs. 40,00,00,000 and Party B borrowing U.S. $10,000,000.

Periodic Payments

Assuming the LIBOR for the first period is 4%, Party B must pay to Party A half (six months’ interest) of 4% on the U.S. $ 10,000,0001 notional, or the U.S. $200,000.

Party A will pay to Party B a fixed rate of 3% (half of 6% fixed) on Rs. 40,00,00,000 notional, or Rs. 1,20,00,000.

Note that these payments are not netted as in interest rate swaps because they are in different currencies, as Party A needs to receive U.S. dollars to pay its U.S.-dollar-denominated interest payments, and Party B needs Indian rupees to pay its Indian-rupee-denominated interest payments.

At swap termination, the counterparties will exchange the notional principals again.

Party A will pay Party B Rs. 40,00,00,000 and Party B will pay Party A U.S. $10,000,000.

Note that the notional principal is exchanged at the initiation of the swap at the prevailing exchange rate.

Similarly, the notional principals are exchanged at the termination of the swap on the basis of the exchange rate prevailing at the time of initiating the contract.

If the currency values have changed in the meantime, one party will need more of its own currency to pay the notional principal.

For example, if the rate has changed to the U.S., $1 = Rs. 41 at the termination of the contract. Party B will receive Rs. 40,00,00,000 from the swap but will need Rs. 41,00,00,000 to pay the U.S. $10,000,000 to Party A. Thus, a currency swap involves currency risk.

Example 1: Company of A, a British manufacturer, wishes to borrow the U.S. dollar at a fixed rate of interest.

Company B, a U.S. multinational, wishes to borrow sterling at a fixed rate of interest. They have been quoted the following rates per annum:

| Company | Sterling | Dollars |

| A | 11.0% | 7.0% |

| B | 10.6% | 6.2% |

Design a swap that will net a bank, acting as an intermediary, 10 basis points per annum and that will produce equally gain per annum for each of the two companies.

Solution: The spread between the interest rates offered to A and B is 0.4% (40 basis points) on the Sterling loan and 0.8% (80 basis points) on U.S. Dollars loans.

The total benefits to all the parties should be:

0.8% – 0.4% = 0.4% or 40 basis points

Possible to design a swap with 10 basis points to the intermediary and equal points benefits to each company, i.e., 40 – 10 = 30 basis points divided by 2 is 15 basis points each.

Company A borrows 11% Sterling from outside lenders. Company B borrows 6.2% U.S. Dollars from outside lenders.

Intermediary borrows 10.45% Sterling from B and lends 6.2% U.S. Dollars to B. Intermediary borrows 6.85% U.S. Dollars from A and lends 15% Sterling to A.

Net effect:

Company A = -11 + 11— 6.85 = —6.85

Company B = -6.2 + 6.2 – 10.45 = -10.45

Intermediary = -11 + 10.45 – 6.2 + 6.85 = -0.55 + 0.65 = 0.10

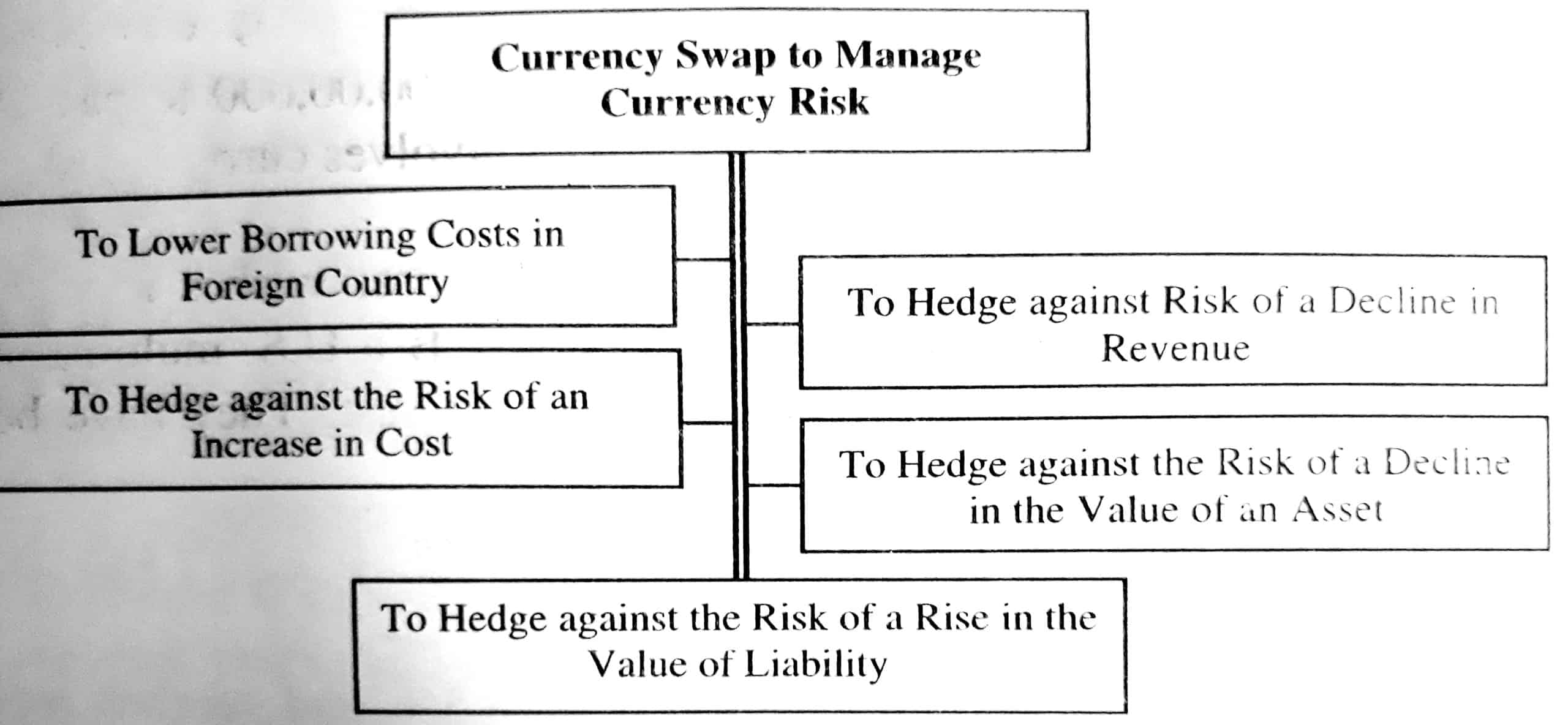

Currency Swap to Manage Currency Risk

Following are the ways by which currency risk is managed by currency swaps:

To Lower Borrowing Costs in Foreign Country

Interest rate swaps can be mutually beneficial if there is a comparative advantage for the two parties in one market over another.

The rationale for currency swaps is similar: one party has a comparative advantage in borrowing in one currency while another has an advantage in the other.

For example, suppose a prominent Indian company (say, TISCO) wants to raise funds in the USA.

At the same time, a prominent American company, say, Jacobs Engineering wants to borrow Indian rupees for a project in India.

TISCO, though a blue-chip in India, may not be well known in the US debt market and would therefore have to pay a higher rate of interest than its credentials would otherwise warrant.

Similarly, Jacobs Engineering may not receive a rate of interest in India that truly reflects its credit rating because of the obscurity of the ‘name’ in India.

It would be beneficial to both companies if TISCO borrows in rupees, Jacobs in dollars, and the two then swap the liabilities.

Sometimes, the comparative advantage could run in the opposite direction. A British company might have already borrowed heavily in the sterling bond market.

As a result, the market may demand a premium on further borrowings, as they would not prefer a concentration of holdings in one company.

On the other hand, say because it is a well-known multinational, it may be able to raise funds relatively cheap in the Indian rupee debt market because it has no previous exposure.

For example, TK, an Indian company, and J, an American multinational, are both contemplating raising funds.

J, by virtue of its larger size, greater diversification, etc., has a better credit rating than T in both markets.

The rates at which the companies can borrow are as follows:

T needs dollars, while J needs rupees.

The difference is 1% in India but 3% in America. Both parties stand to gain by the following arrangement through M, a middleman. (Assume Rs. 40 = $1)

- T will borrow in India a sum of Rs. 40. crore at 19%.

- J will borrow $10 million in the USA at 6%.

- Both parties enter into a swap on the following terms:

- The principal sums are exchanged, i.e., T pays J Rs. 40 crores and receives $10 million.

- T will pay M dollar interest at 8.5% and receive rupee interest at 19%.

- J will pay M rupee interest at 17.5% and receive M dollar interest at 6%.

The cash flows are shown in the table below:

| Party | Interest Outflow on Loan (1)% | Swap Outflow | Swap Inflow | Net Flow |

| T | Rs – 19.0 | $ – 8.5 | Rs + 19.0 | $ – 8.5 |

| J | $ – 6.0 | Rs – 17.5 | $ + 6.0 | Rs – 17.5 |

| M | – | Rs – 19.0 | Rs + 17.5 | Rs – 1.5 |

| $ – 6.0 | $ + 8.5 | $ + 2.5 |

T and J have both achieved a lower cost of capital than if they had borrowed directly in the other currency.

M gains 2.5% in dollars and loses 1.5% in rupees, producing a net gain of 1%. (However, it should be noted that M bears an exchange rate risk.

It is possible to arrange the payments differently with the swap parties bearing some or all of the risk.)

The differential in rates was 3% in the USA and 1% in India; this left a gap of 2% to be shared as gains by the parties to the swap transaction.

In the above transaction, T gains 0.5% (by effectively borrowing at 8.5% instead of 9%), J gains 0.5% (by borrowing at an effective rate of 17.5% instead of 18%) and M gains 1% (+ 2.5% in dollars, – 1.5% in rupees),

To Hedge against Risk of a Decline in Revenue

Consider U.S. Apple, a U.S.-based firm that exports apples and sells them for yen in Japan. An abbreviated form of its income statement is:

Revenues = PxQ – Expenses

= Expense / Operating Income

where,

P = Price, the firm receives for the apples it sells in Japan (¥),

Q = Quantity of apples it sells in Japan, and expenses are in U.S. dollars

The goal of U.S. Apple is to maximize its dollar profits – typical for a U.S.-based firm. U.S. Apple is exposed to the risk that the $/¥ exchange rate will fall.

If the $/¥ declines, the dollar value of the firm’s yen revenues will be less, and its dollar profits will be less.

U.S. Apple can use a fixed-for-fixed currency swap to hedge its risk exposure.

It can estimate its yen-denominated revenues for the next several years and agree to pay fixed yen and receive fixed U.S. dollars in each of the next several years.

U.S. Apple will still be exposed to the risk of fluctuation in the number of apples it sells in Japan.

The number of apples it can sell in Japan will vary as its crop size (in the United States) varies, as the selling price of apples grown and sold in Japan varies, as the prices of other competing fruits in Japan varies, as import/export laws change, and as tastes change in Japan.

To Hedge against the Risk of an Increase in Cost

Chocoswiss is a Swiss manufacturer of liqueur-filled chocolates.

It must import all its liqueurs from France, and it pays for the liqueurs in euros. However, it sells its product in Switzerland only.

Chocoswiss wants to maximize its profits, which are denominated in Swiss Francs (SFR). An abbreviated version of Chocoswiss’ income statement is:

Revenues (in SFR) = Expenses (a significant portion is in euros) / Operating Income

Chocoswiss faces the risk that the SFR/ will rise. If the SFR/ rate rises, then the SFR cost of its imports will rise.

As costs rise (denominated in SFR), SFR-denominated profits for Chocoswiss will decline.

To hedge its currency risk exposure, Chocoswiss can use a fixed-for-fixed currency swap in which it pays SFR and receives euros. There is no need to exchange principal amounts.

To Hedge against the Risk of a Decline in the Value of an Asset

Suppose a U.S. company has a three-year £50 million investment (an asset) that yields 7% annually (in GBP) and pays interest twice per year.

The current exchange rate is $1.60/£. The U.S. corporate treasurer thinks that the dollar will strengthen against the pound sterling.

Equivalently, this means that the dollar value of the GBP will decline (the $/£ exchange rate will decline), which means that the dollar value of any GBP-denominated assets will decline.

If the treasurer is correct, each future interest inflow of £1,750,000 will purchase less than $2,800,000.

For example, if the exchange rate is $1.50/£, the interest payment of £1,750,000 will purchase only $2,625,000.

However, because the current three-year interest rate in the United States is 7.40%, the treasurer does not want to swap each subsequent interest payment of £1,750,000 for only $2,800,000.

Not only will the decline in the value of the GBP mean that the value of the interest rates will be less, but the dollar values of the U.S. firm’s investment decline, too.

The treasurer finds a swap dealer willing to swap interest payment^ each six months £1,750,000 for $2,940,000 over the next three years.

In addition, there will be a final swap of £50 million for $80 million. Under this swap, the U.S. company has transformed its three-year £50 million investment that yields 7% into a three-year $80 million investment that yields 7.35%.

For example, consider a Japanese company that owns some real estate in the United States; i.e., the Japanese company has a dollar-denominated asset.

If the ¥/$ exchange rate declines, the value of this asset, in yen, will decline. To hedge, the Japanese company can buy yen futures or forwards.

Alternatively, the Japanese company can enter into a swap, paying dollars and receiving yen.

To Hedge against the Risk of a Rise in the Value of Liability

If the value of a firm’s liability rises and its asset values remain unchanged, it follows that the value of the firm’s stock must decline.

This must be the case because:

Assets = Liabilities + Owners’ Equity.

Suppose a U.S. company has a two-year debt (a liability) of 100,000,000 at 7.7% annually, and interest is paid quarterly.

The current exchange rate is 0.9720/$. The U.S. corporate treasurer’s staff is predicting that the dollar will weaken against the euro (i.e., the /$ exchange rate will fall).

This is equivalent to predicting that the $/ rate will rise. If the dollar price of the euro rises, then the dollar-denominated value of this firm’s liability will rise.

If the staff is correct, each future interest payment of 1,925,000 will cost more than $1,980,453.

For example, if the exchange rate changes to 0.9400/$, the interest payment of 1,925,000 will cost the firm $2,047,872;

The treasurer finds a swap dealer willing to swap quarterly cash flows of 1,925,000 for $2,004,750 over the next two years.

In addition, there will be a final swap of 100,000,000 for $102,880,658. Under this swap, the U.S. company has transformed its two-year 7.7% debt for 100,000,000 into a 2-year $102,880,658 debt with an interest rate of 7.79%.